Why an article on strength training and cycling? Let me begin by

zooming out on the encumbrances of hyper-analyzing high-performance

sports in our modern era. Aside from bicycle racing, only Formula One

and America’s Cup Sailing come to mind, rivaling in their access to

performance analytics data. My view is biased, having been both a

competitive cyclist and worked with teams like Emirates Team New

Zealand and Lotus Racing in my professional career. Although my work

focused on branding, content creation, and consulting, I gained

unique insights into their infrastructure needs.

America’s Cup and

Formula One Racing each require massive computing power—so

much so that these teams must have strategies to monitor the

athletes, the automobiles, and the racing equipment. The data and

computing requirements are mind-bending as they cover physiological

data, telemetry analysis, aerodynamics, fuel consumption, wind speed,

sail and trim positions, hydrodynamics, weather, load sensors,

communications, and so much more.

Professional bicycle

racing is undoubtedly high-tech, though not to the extent of the

programs above. Modern cyclists, from local club riders to regional

racers, benefit from trickle-down technology. With a “one-click

payment” option on Amazon, remarkably similar power meters and

various gadgets utilized in the Grand Tour can arrive on your

doorstep. Each item seamlessly connects with our head units

(bicycling computers), where we can sense and monitor our pedaling

dynamics, power data, pulse oximeter data, HRV, temperature, speed,

averages, and much more.

So, we put our heads

into the data. We sign up for apps like Strava, Zwift, and

TrainingPeaks to help us analyze and measure our data from each ride.

We have access to countless coaches, forums, articles, and YouTube

videos that teach us how to optimize our programming based on our

unique physiological data over time to improve our performance and

enjoy our experience on the bicycle.

Why

Chase the Margins First?

Why is Formula 1,

Sailing, and World Tour Cycling relevant? Because it’s entertainment

doing what it’s supposed to do: they entertain and inspire us because

those arenas are entertainment businesses first, then sports. In

pursuing performance, we easily become distracted by the science,

cost, and time that these multi-million dollar enterprises throw off

while seeking millisecond gains. With that in mind, it leaves me

wondering why so many of us spend so much time and effort making a

simple thing so much more complex. Why not take a step back and

look at the fundamentals? Then, we can add what’s in the

margins if we are so inclined.

Now, what are the

fundamentals of our sport? Let’s ask ourselves how much power over

a given time is required to establish a breakaway, win a field

sprint, time trial to a solo victory, or beat our best buddies to the

city limit sign. What is it you wish to do, or that you enjoy most

from your time on the bicycle? Even club riders like to win city

limit sign sprints or chase Strava KOMs.

Cycling is often

regarded as an “endurance” sport, when actually the winning

part is almost always based on one, usually several, explosive

efforts. Strength training, as an integral part of our entire cycling

program, easily equates to an advantage totaling dozens of marginal

gains. With a personal passion for the sport of bicycling, we who

represent the sport are not usually strength athletes, and can

therefore benefit massively by improving our absolute strength before

we waste time chasing other nuanced marginal gains.

Many of us, myself

included, care too much about piles of miles and numbers that don’t

matter enough. When Mark trained me roughly 30 years ago, he

rearranged the furniture in my head to show how this works. We were

pretty cutting-edge in how he applied strength training to cycling.

Having tried numerous times in fits and starts to come back to the

sport, I’m not sure of any other path that has surpassed what I

learned in his gym so many years ago. Back then, we did not have a

supercomputer in our pocket connected to YouTube, Reddit, and all the

micro-blogs “freely” giving us distracting advice on

maximizing our performance. How much better are we today, really?

Don’t

sacrifice the X-factor at the altar of marginal gains

While we’re looking for

our marginal gains and spending thousands of dollars on carbon

wheels, power meters, and electronic shifters, there is a gain I do

not believe to be so… marginal. By simply increasing our absolute

strength, we outperform most of what we chase in pursuit of marginal

gain. Increasing one’s ability to push more weight under the bar is

the X-factor for those who want to be more explosive in their

sprints, attain higher top speeds, increase average speed, and be

less prone to injury – or, at the very least, make your club rides

more fun in the space between the breweries, which I absolutely

believe to be a critically important aspect of cycling.

Look, I get it. I love

the data, too. And I’m not likely to give that up. But I believe we

can enjoy cycling more and have a healthier outlook for ourselves,

those around us, and the sport by adding strength training to our

cycling agenda. Chasing those marginal gains alone is a long road,

often leading to analysis paralysis and burnout.

OK, here’s a nugget for

those still wanting to put their heads into the numbers. What’s your

current training strategy for increasing your FTP (Functional

Threshold Power)? I’d start with what a wise man once told me: “Cut

your mileage back, way back. Get under the bar and increase the

horsepower of your motor.” It’s not science fiction to believe

improving absolute strength may still today be the X-factor for one

who wishes to dramatically change their performance on the bicycle.

Here’s a little more

context on where I’m coming from with this.

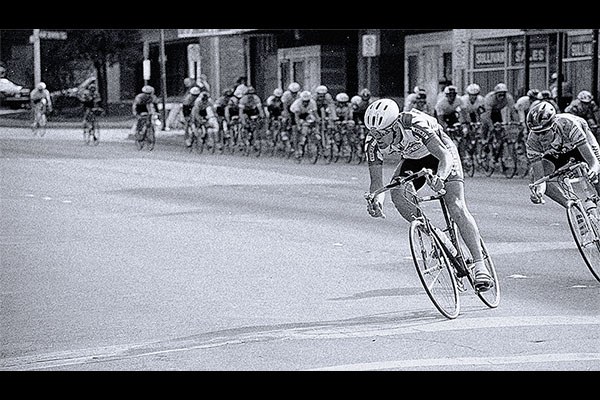

Fast

But Not Strong Enough: Flashback to a Criterium in Dallas, circa 1990

It became so clear in

that moment, choking down the August air in Dallas, Texas, during the

hottest point of the day, that he was just… stronger than me. Not

only a better racer. But stronger.

A 90-minute criterium –

the Pepsi games – at Flagpole Hill – circa 1990: I’d bitten off

more than I could chew. Sometimes, you can get away with being a

lesser-skilled bicycle racer if you have the muscle to fall back on.

But I was young and cocky – I might have said something about his

receding hairline (you say things to piss off your opponent, or you

confuse them, or whatever it takes). But if you piss off the athlete

who is stronger than you, he might beat you. Chris Hipp was stronger

than me. If he is also tactically superior, you might as well drink a

bottle of radiator fluid because you just failed the class you

enrolled in.

The criterium went

counterclockwise. The start and finish zone were at the top of

Flagpole Hill. Flying down Lanshire Drive at 40 miles per hour, left

at Goforth Road, followed by a left hairpin onto Doran Circle to

scrub off any good speed we carried into the hill. In a 53×14 gear,

44 pedal revolutions are used to move your body and the bicycle to

the finish line.

We were away in a

group, the advantage was mine. A teammate even blocked him from the

outside line, forcing him to interrupt his line. All my training went

into my legs – digging to the depth of my available power when

halfway up the hill, he just blistered past me. To this day, I can

see it in 4k detail. Chris simply applied more pressure to his pedals

than I was able to. But it was controlled and fluid. He used his

bicycle and his bars as a lever. You could always see this “attitude”

in his Form. His movements were in sync, from his legs, core,

shoulders, arms, elbows out, and nose, pointing just above the top of

his front tire. Eyeballs up and out towards the finish line,

launching the bicycle forward in one continuous explosive action.

The secret was right

there on full display if we could just see it, yet we bicyclists try

to overcome it by adding piles of miles to the agenda. Chris Hipp’s

absolute strength was greater than mine relative to his body weight,

and sometimes it’s as simple as that.

Less

Strength = Less wins. A Pattern Emerges.

Losing was something I

took very hard. But at that time, a new kind of terror shredded

through me. If you can’t beat the local star ten years your senior,

how can you rationalize forward progression in your performance with

the same programming you’re doing today? On that day, I did not

think I could ever beat him – not even if my life depended on it.

Soon after this painful

defeat, we raced again. A pro race in Tyler, Texas, where I’d gotten

away in the road race and took second. And second, again, the next

day in the criterium. I’d only beaten Chris because I had made the

breaks, and he had not. Had he made them, he’d have won both of those

also. Second place was becoming too familiar a pattern.

After those races in

Tyler, Chris approached me, congratulated me on my losing both of

those races, and asked me to join his team, which I did. He taught me

every nuance of bicycle racing: the strategy, the techniques, and the

importance of never quitting. Of the many things I learned, there are

two quotes from him that sum up the reason for this essay in the

first place:

1. “Now, Ronan,

listen carefully because this is the straightforward order of things

in bicycle racing. It’s Form, then power, then speed,

then stamina, then strategy. In that order!”

2. “If you love it,

never ever, ever, ever ever quit.”

There are many stories to

tell, but since this is Mark Rippetoe’s website, let’s fast-forward a

couple of years…

MSU

Cycling Team and Meeting Rippetoe

Dr. Robert Clark and

his band were determined to create what would become the most winning

collegiate bicycle racing team on Earth. I met with Dr. Bob and the

MSU cycling board on a Saturday, and I was given an unforgettable

opportunity to become part of the collegiate cycling program. During

my early days at MSU I was still grappling with how to program my

training to improve my foundational strength. I told Dr. Clark about

a recent stay at the Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs.

From all my work at the Springs, one person stood out to me. We’d had

a chance to attend a strength training clinic with Coach Harvey

Newton.

The pain inflicted on my body by Coach Newton revealed the weak

links. In listening to my body through the lens of first principles,

it was undeniable that a change in my muscle tissue was occurring.

You can feel the pain in the neglected places, enough to identify

crucial areas of weakness in the kinetic chain. This I believed to be

the edge I was looking for, but I’d only been exposed briefly to

strength training and, back in Texas, found myself looking for a

place to begin.

I remember this

conversation with Dr Clark vividly. I was part of this new team and

talked with him privately in his office. I had the availability of

every resource I needed from the town known for creating and

sustaining the largest mass start cycling event of its time – the

Hotter’n Hell Hundred, in Wichita Falls. While listening to my

“discovery” at the training center, Dr. Clark eased back in his

chair and said, “Sounds like you need to meet Rippetoe.”

To be continued. . .

Discuss in Forums

Credit : Source Post